This is a revision of a lecture I presented on 20 April 2017 at Hope College in Holland, MI. The lecture was sponsored by the St. Benedict Institute.

Good evening. Happy Easter to you all.

I say this assuming that you acknowledge this past Sunday to have been the feast of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. Were I delivering this talk in seventh-century Northumberland, I might not have assumed this, for the calculation of the date of Easter was then a controversy. Discord between two groups of missionaries over it threatened the survival of Christianity within the newly and incompletely converted kingdom. The first mission came from Ireland by way of Scotland; it had established the monastery at Lindisfarne and followed the practices of St. Columba. The newer mission was sent from Rome by St. Gregory the Great; its monasteries at Wearmouth and Jarrow were only forty miles from Lindisfarne.

In principle, both missions celebrated the Resurrection on the first Sunday after the first Full Moon after the Vernal Equinox, as the Council of Nicæa had mandated. This method of calculation is beautifully simple; it involves the sun, the moon and the seven-day week: the three means of telling time established by God at the Creation of the World. In a fallen world, however, things are seldom beautifully simple; what is correctly reckoned to be the first Sunday, or the first Full Moon, or the Vernal Equinox was disputed.

In AD 664, King Oswy of Northumberland convoked a synod at Whitby to settle the matter. Colman, the Bishop of Lindisfarne, argued:

The Easter that I keep I received from my elders, who sent me hither as bishop; all our forefathers, men beloved of God, are known to have kept it after the same manner. This may not seem to any contemptible or worthy to be rejected.

Wilfrid of York, speaking for the Roman mission, said:

The Easter that we observe we saw celebrated by all at Rome, where the blessed apostles Peter and Paul lived, taught, suffered and were buried. We saw the same done in Italy and in France when we traveled through those countries for pilgrimage and prayer. We found that Easter was celebrated at one and the same time in Africa, Asia, Egypt, Greece and all the world, wherever the Church of Christ is spread abroad, through the various nations and tongues, except only among these. Do you think that their small number, in a corner of the remotest island, is to be preferred before the Catholic Church of Christ throughout the world? Though Columba was a holy man and powerful in miracles, yet should he be preferred before the most blessed prince of the Apostles?

King Oswy, reasoning that it was St. Peter rather than St. Columba who held the keys to Heaven, ruled in Wilfrid’s favor. Colman returned to Ireland; the monks remaining at Lindisfarne accepted the royal decision.

Both Colman and Wilfrid are venerated as saints. The arguments that they presented more than thirteen centuries ago yet resound. Their disagreement was not merely over whether Easter should be celebrated this week or the next; it was over the root and the sway of religious tradition; over whether an outlying tradition should be conformed, and to what, and by what authority. Both claimed to uphold ancient custom; Wilfrid added to his argument the weight of universality and consensus, and the authority of St. Peter.

*******

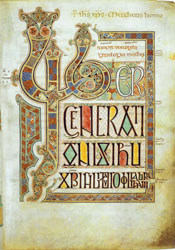

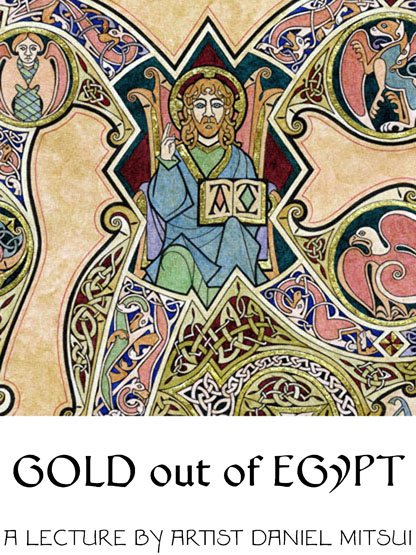

One of the greatest works of Christian art was made in this very setting of seventh-century Northumberland: an Evangelary written and illustrated at Lindisfarne just a few decades after the Synod of Whitby. Its pages contain some of the finest drawings ever made. Its scribe was the Saxon monk Eadfrith, who later became the Bishop of Lindisfarne. In matters of ornamental and calligraphic design, his work has never been surpassed.

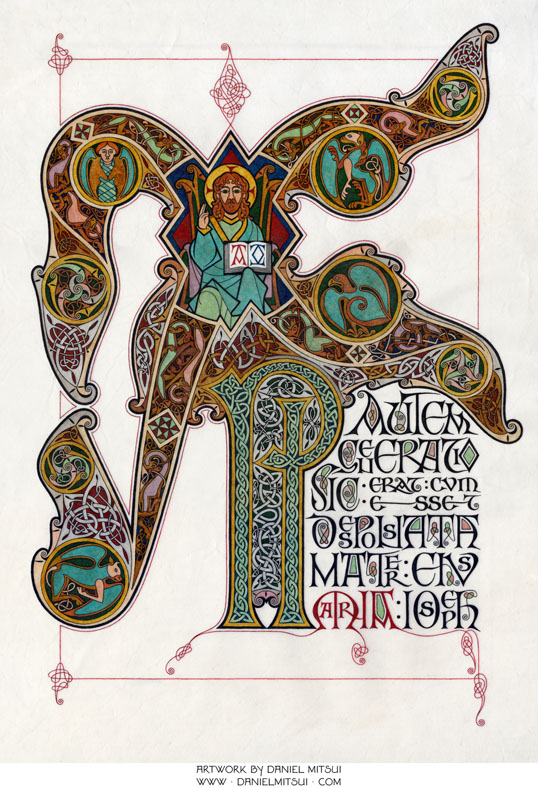

Seeing a reproduction of a page from the Lindisfarne Gospels when I was about fourteen years old was a pivotal event in my artistic development. The impression was similar to that made on a 12th-century writer who studied a similar manuscript: You will make out intricacies so subtle and delicate, so exact and compact, so full of knots and links, with colors so fresh and vivid, that you might say that all this was the work of an angel, and not of a man. I tried for years to interpret this style; it took about fourteen before I was able to make what I consider a successful imitation.

Now, long after that, it is part of my artistic repertory; I can draw these patterns freehand. The Lindisfarne Gospels no longer seems to me like a thing that fell out of heaven. But I am just as fascinated to consider it as a thing made by men, to consider just how many different men, from how many different nations, were needed for such a work of art to be possible.

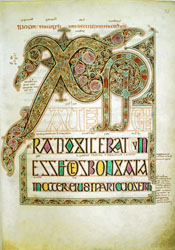

Consider the page from the Lindisfarne Gospels that displays the eighteenth verse of the Gospel of St. Matthew. The author is a Hebrew who probably wrote in Greek. The words are the Latin translation made by St. Jerome: Christi autem generatio sic erat cum esset desponsata mater eius Maria Ioseph. The first, Christi, is abbreviated as Chi-Rho-Iota; the letters are Greek, not Latin. Greek Christian scribes have always abbreviated certain holy names, or nomina sacra; Eadfrith did the same in this Latin manuscript.

He wrote the small letters in Insular Majuscule, a striking script invented by Irish monks. It derives ultimately from the uncial script invented by Christian scribes in Egypt who used curving Greek penstrokes to write Latin letters. Uncial was the first peculiarly Christian handwriting; the faithful throughout the Latin-speaking world adopted it to distinguish holy manuscripts from pagan literature.

The display capital letters of the Lindisfarne Gospels have an unmistakable resemblance to Germanic runes. Runes were known at Lindisfarne; they were even used to carve the nomina sacra on the reliquary casket of St. Cuthbert. Patterns of knots, spirals and keys; and interlaces of elongated beasts and birds decorate the manuscript. These are motifs from Celtic and Germanic art that predate the Christian missions.

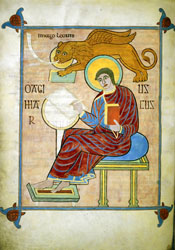

The pages depicting the four Evangelists, however, resemble mosaics from Rome or Byzantium or Antioch. Eadfrith likely based their composition on pictures in an illustrated manuscript brought by missionaries from one of the Mediterranean urban centers of early Christianity.

It was through small, portable objects such as books that iconography spread; a missionary, obviously, cannot carry a basilica decorated with mosaics with him into the wilderness. He can carry a great many books containing a great many pictures. In the monastic art of Northern Europe, fascinating combinations of Hellenistic, Syrian and Byzantine traditions are encountered. The influences can be distinguished as late as the twelfth century, and vary from monastery to monastery. This is because their libraries held books from all over the Christian world, which served as models for the resident artists.

Cruciformally arranged ornament fills five pages of the Lindisfarne Gospels. Art historians call these carpet pages; one, Volkmar Gantzhorn, has proposed that they were inspired by actual carpets woven in Christian Armenia. Carpet pages appeared in Northumbro-Irish manuscripts about the time that Theodore of Tarsus arrived at Canterbury to become its archbishop in AD 669. Perhaps he carried, either in his memory or in his baggage, the tradition of the Oriental carpet as far as Lindisfarne.

Other scholars see in the carpet pages an imitation of Coptic art; several intriguing early medieval documents mention Egyptian monks living in Ireland. A Psalter from this time, lined with Egyptian papyrus, was pulled intact from an Irish bog eleven years ago.

The Lindisfarne Gospels is thus a work of sacred art to which Germanic, Celtic, Roman, Greek, Hebrew and possibly Armenian or Coptic Christians contributed. It pages illustrate the universality invoked by St. Wilfrid, whose words would have been fresh in the memory of the monks at Lindisfarne; here, at one and the same time, is the art of Africa, Asia, Egypt, Greece and all the world, wherever the Church of Christ is spread abroad, through the various nations and tongues. It was never more beautifully made than in a corner of the remotest island.

*******

It annoys me to know that, upon seeing this page, most people would simply say: Oh, how Irish. A few would call it Celtic instead. And while that is not an inaccurate description, it is a meager one. This art is popular in the present day, not as an expression of universal Christianity, but of Irishness or (more commonly) pseudo-Irishness. You often see it on pub signs and knickknacks and other bits of paddywhackery; you rarely see it on sacred artwork. I cannot imagine a new church being decorated in this manner, unless it were intended for Irish immigrants. Certainly I am grateful to see this art linger at all, but I lament the loss of the idea that it belongs to everyone.

It seems that national identity, rather than religious faith, is the most strongly felt motive nowadays for holding to tradition. The notion is that a style of art or architecture, folk music or dance, ceremonial dress or cookery is important to remember because it is part of what makes a person Irish or Polish or Mexican or Dutch. That is praiseworthy, except when religious faith itself is considered an element of national identity, as though it were the smaller and less important thing.

Early examples of this disordered priority can be found during the Gothic Revival; the architect Eugene Viollet-le-Duc did a great service to the universal Church by restoring the reputation of Gothic art and architecture after centuries of calumny and neglect. But he did so because the cathedrals made him proud to be French; he was an anti-clericalist who played down the religious motivation of medieval artists, and even read into their work coded revolutionary messages.

Gothic art and architecture indisputably began in France, but they rapidly spread throughout Christian Europe. Their principles, derived from the theology of St. Augustine of Hippo and of Dionysius (author of the Celestial Hierarchy), made possible the ordering of the various monastic traditions into a coherent system, the basis for sacred art from England to Spain to Bohemia.

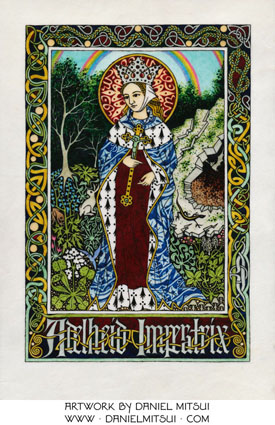

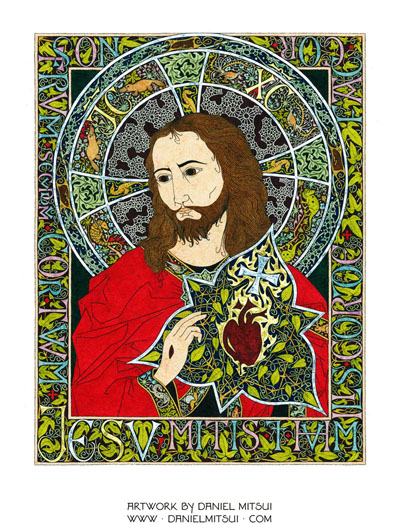

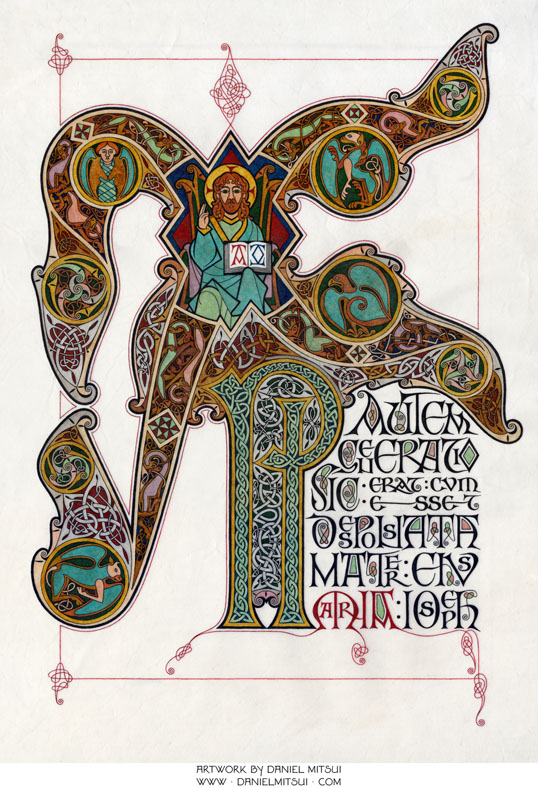

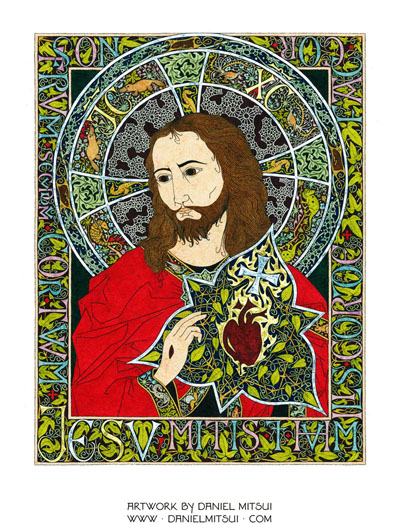

This International Gothic is the basis for almost all of my own artwork. I consider it an important task to demonstrate that Gothic art is not defined by nationhood, nor by a period of history past, but rather by Christian principles that are everywhere and enduringly true.

One of those principles is to offer to God the very best. Artists of the International Gothic deferred to the Church Fathers when composing pictures, but used every artistic form they knew to make them beautiful. The painters of late medieval Italy borrowed from the art of Mamluk Egypt, using Arabic script (spelling gibberish) to decorate the trims of the Virgin Mary’s robes. In the Adoration of the Magi altarpiece by Gentile da Fabriano, the haloes of the Virgin Mary and St. Joseph are imitations of Islamic gold platters. The painters of late medieval Flanders depicted the Virgin Mary sitting in thrones hung with Oriental damasks, Oriental carpets beneath her feet.

That Oriental carpets would inspire Christian artists as seemingly different as Eadfrith of Lindisfarne and Jan Van Eyck is not happenstance but a sign of shared principles. In my religious drawings, I try to show the affinity of Northumbro-Irish art and International Gothic, combining elements of both.

*******

As much as I lament that these knots and spirals would not be found in a church nowadays except as an expression of Irishness, I lament more that a church nowadays is likely to contain no artwork at all. We are living in a time comparable to the iconoclastic crises; contempt for tradition and sacred art is encountered at all levels of the Church.

Moreover, contemporary secular society is decidedly antitraditional. Those who mass-produce and peddle its culture profit by arousing the desire for novelty; things that are made to endure or to live with can only be sold once. Its music and art exist primarily as electronic simulacra. These can be sent across the world within seconds; bound to no particular place, they go to every nation and move them toward sameness. I do not know if such things can properly be called culture; I do not know if they can even properly be called things. A similar movement toward a postnational world is made in political and economic matters. The rules of national sovereignty are reduced to legal fictions, just as the marks of cultural identity are overwritten or erased.

Unsurprisingly, this provokes a reaction. All over the world, people are concerned to protect their self-determination and cultural identity from foreign influences, from invasive ways that are not theirs. That is to say, that are not theirs as Frenchmen or Englishmen or Germans or Americans. In such a time, when nationalism provides the motive to preserve tradition, and postnationalism the motive to destroy it, it seems that anyone who is a traditionalist in matters of religion or culture or art should and must be a nationalist as well.

The curious thing, however, is that in the history of Christianity, nationalism is not an especially traditional idea. A distinction between nations certainly is as ancient as the Tower of Babel, where the language of the whole earth was confounded: and from thence the Lord scattered them abroad upon the face of all countries. But the idea that nationhood be the foremost way for a man to understand his identity, his place in history and in the world, began in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The choice presented between nationalism and postnationalism is a false dilemma; there is older way, and that is what is actually expressed in works of art such as the Lindisfarne Gospels and Chartres Cathedral. It is the idea of Christendom: that a man should understand his place in history and in the world not foremost as a member of a particular nation, but rather as a member of the universal Church. This is the way that once was maintained by the Church, and that naturally would be yet, were it not for the failure of its institutional authorities to stand fast, and hold to the traditions they have learned. Perhaps artists can take up the task, if churchmen will not, of reviving this magnanimous idea.

This idea of Christendom does not destroy the particular genii of nations, but neither does it provoke them to battle against each other. It rather establishes principles by which they may together praise the same God. Moreover, it establishes principles by which the Christian tradition may withstand foreign influences; not by barring them entry, but by converting them to its same sacred end, by staking upon whatever is true or good or beautiful in them a legitimate claim.

*******

The word Christendom is often used to refer to the political and military aspect of the universal Church, one embodied by the converted Roman Empire and by the confessional states that succeeded it. I am not really speaking about that, for I neither possess nor know any means that could plausibly restore it. If I did, I would not trust anyone alive today to exercise it well, without committing some terrible injustice or other.

I am rather speaking about a religious force for communication between nations and the partaken culture that it inspires. This is older than the conversion of Constantine, indeed as old as the Church. Consider the miracle of Pentecost, which the Church Fathers contrasted to the divine intervention at Babel:

And they were all filled with the Holy Ghost, and they began to speak with divers tongues, according as the Holy Ghost gave them to speak. Now there were dwelling at Jerusalem, Jews, devout men, out of every nation under heaven. And, when this was noised abroad, the multitude came together and were confounded in mind, because that every man heard them speak in his own tongue. And they were all amazed and wondered, saying: Behold, are not all these that speak, Galileans? And how have we heard, every man our own tongue wherein we were born? Partians and Medes and Elamites and inhabitants of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the parts of Libya about Cyrene, and strangers of Rome. Jews also and proselytes, Cretes and Arabians; we have heard them speak in our own tongues the wonderful works of God.

The miracle was not to make all these different men into Galileans, nor to give them understanding of a single language, whether that of Galilee or that of Eden. Christianity did not erase the distinction between nations or tongues, or move them toward sameness; it rather made the wonderful works of God intelligible to them all and thus ended the privilege of any; as St. Paul wrote: There is neither Gentile nor Jew, circumcision nor uncircumcision, Barbarian nor Scythian.... Christ is all and in all.

*******

As the Church has, from the day of Pentecost, served to unite nations, so has the ancient enemy worked to divide the Church. I see in the International Gothic an expression of Christendom; but obviously, it has been limited to the patriarchate of Rome. By the time the Gothic cathedrals were built, the patriarchies of Antioch and Alexandria and Byzantium were separate. Nonetheless, within the patriarchate of Rome, believers out of divers nations were culturally united, despite linguistic differences and historic enmities. Across Christian Europe, sacred music and art and architecture were ordered to a common liturgical tradition that used Latin as its lingua sacra, one strongly influenced by Benedictine monasticism and the legacy of St. Gregory the Great.

One aspect of this tradition is the preeminence of Rome itself, the theological basis for which is the promise made to St. Peter by Jesus Christ: I will give to thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven. As Wilfrid of York mentioned, Rome is where the blessed apostles Peter and Paul lived, taught, suffered and were buried. Its bishop is the inheritor of their authority. Because of this, there is a legitimate and necessary Romanity to the universal Church, which was recognized even in seventh-century Northumberland. It is important, however, to recall the fullness of Wilfrid’s argument. His was no blind appeal to authority; it was not sufficient for him to say that his way was the Roman way, but rather that it was also the French and Italian and African and Asian and Egyptian and Greek way. His appeal was to antiquity, universality and consensus: the very marks of authentic tradition identified by the Church Fathers.

Had Wilfrid believed that Romanity were altogether independent of these, he would not have bothered to mention them. For him, Romanity was a means of protecting what was revealed to the Apostles. This revelation is not esoteric; it is knowable to everyone through scripture and tradition. Insofar as there is a necessary key to understand it, it is the gifts of the Holy Ghost received in the sacraments of Baptism and Confirmation.

I can hardly imagine a more dangerous error than to think that the bishop of Rome were privy to a newer or fuller revelation; that he were the creator of tradition rather than its protector. If the faithful were to fall into this error, what would they do if the Roman way ceased to be the ancient and universal way, if the Roman way were the way that defied the Catholic Church of Christ throughout the world?

*******

This is hardly a fantasy. In the realm of sacred art, it has been so for centuries. After the unity of the patriarchate of Rome was shattered by the wars of Reformation, a new idea emerged within the Catholic Church, an idea that has largely directed its culture and art ever since. This is the idea of an overruling Romanity, altogether independent of antiquity, universality and consensus.

According to this idea, the only mark of Catholic artistic and cultural identity is imitation of Roman custom. This parallels the most exaggerated ultramontanist theology, according to which the only measure of Catholic faith is agreement with the Pope. This idea has grown over the centuries with the concentration of power, over kings and among bishops, in his person. It undoubtedly depends on the technology of mass communication, without which direct papal influence could never be so extensive.

Certain theologians within the Church have so disproportionately taken this idea as to say that Christian knowledge is altogether dependent upon papal infallibility; that neither the agreement of the Church Fathers nor the traditional law of worship has any worth except insofar as it receives papal endorsement.

Ceiling of the Monastery Church at Prüfening

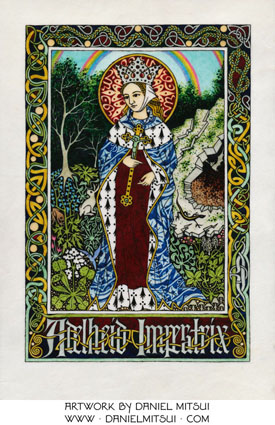

The difference between this and the medieval idea of the Church can be seen in the iconic symbol of the Church itself. Medieval artists personified the Church as a dignified figure called Ecclesia. Usually, Ecclesia is depicted as a woman, crowned and regally dressed, carrying a chalice and a staff of authority surmounted with a cross. Sometimes she is depicted catching in her chalice the blood and water that flow from the side of Jesus Christ crucified, which signify the sacraments of Baptism and Eucharist. Sometimes she is placed opposite an analogous figure representing the Old Testament, as on the portals of Strasbourg Cathedral.

There are more subtle ways of representing Ecclesia: for example, by giving certain of her attributes to the Blessed Virgin Mary. Ss. Peter and Paul together sometimes stand in the place of Ecclesia; according to the medieval doctors, St. Peter signifies the Jewish Church and St. Paul the Gentile Church. Their juxtaposition is therefore not only an expression of Romanity, but of universality as well.

Ecclesia has almost entirely disappeared from sacred art. What has replaced her? What is the new iconic symbol of the Catholic Church? Imagine that I were speaking in some foreign language, no word of which you understood. What single image could I project on the screen behind me, that, upon seeing it, would make you understand that I were speaking about the Catholic Church? Most likely, the answer is one of two things: a picture of the Pope, or a picture of St. Peter’s Basilica.

*******

By St. Peter’s Basilica, I do not mean the fourth-century church erected under the orders of Constantine; that building was knocked to rubble in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries to make way for a new building, the one designed by Bramante and Michelangelo and Bernini.

The distinction between the two Basilicas of St. Peter is important here, for artistic and cultural ultramontanism does not present as its ideal the Roman monuments of Constantine. Nor does it present the paintings in the Roman catacombs, nor the medieval Roman works that show the continuity of sacred art and link it to the continuity of the Petrine succession. In the demolition of the old basilica, more than half of the papal tombs were destroyed, as were twelve centuries worth of frescoes and mosaics, including major works designed by Giotto.

Oil Painting by Francesco Berretta

Copy of a Destroyed Mosaic by Giotto

What artistic and cultural ultramontanism rather presents as its ideal is the Humanist and Baroque art of the new basilica and the Sistine Chapel. These are famous places where Popes are elected and crowned. But to call their art the art of the papacy, and therefore the proper art of the Catholic Church, is nonsensical. Only perhaps a dozen of the bishops of Rome had any role in its creation, and those included some of the most corrupt and impious men ever to sit of the throne of St. Peter. Certainly Adrian VI, the most honest and decent Pope of his era, considered the entire Humanist project a blasphemy and a waste.

Obviously, one Pope does not always agree with another. If an art is proper to the Catholic Church, it is so for being beautiful, true and good; for being holy and universal and apostolic; for being scriptural and traditional. Northumbro-Irish art and International Gothic are abundantly all of these things. What can be said about Humanist and Baroque art?

*******

I am deliberately avoiding the term Renaissance here, as that term is understood too broadly. Its definition is extended backwards to include Cimabue and Duccio, northwards to include Jan Van Eyck and Rogier Van Der Weyden, all of whose work can be explained as the development of Gothic tradition, without any reference to the philosophy that animated the art of Michelangelo. Neither did all Italian artists of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries profess Humanism; Fra Angelico, for example, was a disciple of Giovanni Dominici, one of the prominent critics of the movement.

Humanism attributed to the individual a vast autonomy and dignity and capacity for improvement. Whereas medieval Christianity stressed dependence on divine grace for eternal salvation, Humanism advocated the making of a grand new order upon earth in which mankind might reach its fullest potential. This was to be done by studying and imitating the ancient Greeks and Romans. To the Humanists of fifteenth and sixteenth century Italy, Classical antiquity was the standard against which to weigh and find wanting the culture of medieval Christendom. In grammar, handwriting, architecture, painting and sculpture, they replaced medieval traditions with reconstructions based on ancient models.

Their art excludes almost all stylistic evidence that the medieval centuries ever happened. There is no place within it for the Lindisfarne Gospels, or for Chartres Cathedral. Those the Humanists considered barbaric. It was they who invented the slanderous name Gothic to associate medieval art with the ruiners of Classical Rome.

Medieval thinkers believed that the revelation of Jesus Christ provided the answer to every question and every problem; under the New Testament, there are no longer any important secrets. The larger part of their intellectual energy was spent ordering existing wisdom into encyclopedic works, in art as much as in writing. The Humanists, in contrast, were fascinated by esoterica. They not only saw in Greek and Roman remnants the plans for building a better world; they even aspired to recover the lost language of Eden through the study of hieroglyphics, Hermetic doctrines and Kabbala. They really seemed to believe that the confusion at Babel could be undone by scholarship and archaeology, rather than by the miracle at Pentecost! The Humanists made protestations of faith, but they could never altogether conceal the implicit tenet of Christian insufficiency, even when building colossal churches dedicated to the prince of the Apostles.

Baroque art was not as directly affected by these ideas; its artists rather took the art of the Humanists as their basis. They exaggerated certain tendencies of it and defied others, but never returned to the traditions of the International Gothic. I do not deny that some aspects of Humanist and Baroque art are good and beautiful and worthy of imitation. But neither do I ignore that some aspects are not. The imposition of this art upon the divers nations of medieval Christendom in place of their proper heritage was simply wrong.

*******

It is easy to forget how grating this imposition must have been at the time. The construction of the new Basilica of St. Peter was funded by the peddling of indulgences in Northern Europe; thus it was the immediate provoking cause of the Reformation. Faced with the challenge of Protestantism, the institutional authorities of the Catholic Church did not present to the German and Scandinavian faithful the argument that their heritage, their culture, their art was substantially Catholic, and that keeping it linked them to the Apostles and to the faithful of all nations. Rather, they told them to disregard it and replace it with something new and alien, just to associate themselves with the Pope in Rome.

Had I lived through this, I probably would have reacted like the character of Hans Sachs in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, ranting against sinister foreign influences and urging my people to keep their art holy, German and true. When ultramontanism provides the motive to destroy tradition, and nationalism the motive to preserve it, I can barely fault anyone for favoring the latter. Parts of the international art of medieval Christianity, such as Gothic architecture and blackletter script, lingered within Lutheran Germany longer than under the papacy. This is why, upon seeing these today, many people simply say: Oh, how German.

I see no reason why the basilica designed by Bramante and Michelangelo and Bernini should be the icon of the Catholic Church any more than the Cathedrals of Magdeburg or Halberstadt, or the stave churches of Norway, that were separated from the Catholic Church as a result of its construction. The new basilica is astonishingly big in its physical dimensions, but it reveals an equally astonishing shortsightedness and narrowmindedness; in spirit, it is a very small building.

*******

Medieval art and architecture is magnanimous enough to include the Greek and Roman genii without forcing out any part of the Christian tradition. About AD 560, a Roman statesman named Cassiodorus took religious vows and founded a monastery in the far south of Italy; there, he built a scriptorium in which monks copied books, both sacred and secular, both Greek and Latin, as an exercise of piety. This idea of the monastery as a preservative of culture and learning was taken as far as Northumberland. The monasteries at Wearmouth and Jarrow obtained books from the personal library of Cassiodorus; one of them was the likely iconographic model for the Lindisfarne Gospels.

In Gothic art, Classical wisdom is represented by the sibyls, prophetesses who foretold the coming of Jesus Christ to the Gentiles just as the prophets of the Old Testament foretold it to the Hebrews. The Eritrean Sibyl wrote verses describing the Last Judgment than include an acrostic of the name Jesus Christ; she is the one mentioned in the Dies Iræ sequence. The Triburtine Sibyl interpreted a vision of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child to the Emperor Augustus at the time of the Nativity. The Cumæan Sibyl’s messianic prophecy was quoted in the Fourth Eclogue of Virgil. This is why the poet stood among the prophets in medieval liturgical plays, and in depictions of the Tree of Jesse.

The Moralized Ovid, written in the thirteenth century, applied the method that the Church Fathers used to interpret to Old Testament to the Metamorphoses: its author saw Theseus and Æsculapius as symbols of Jesus Christ. The Augustinian and Dionysian theology that first inspired Gothic art and architecture is profoundly Platonic; the doctors at the Cathedral School of Chartres studied the Timæus reverently.

This all might be mistaken for an early expression of Humanism, but there was an important difference in priority. Medieval Christians believed that the light of the Gospel alone revealed truth, goodness and beauty; insofar as the ancient Greeks and Romans saw them at all, it was through a glass: very, very darkly. Insofar as they possessed them at all, it was as borrowers or thieves, for these properly belong to the Church. Medieval Christians believed that they themselves understood the true meaning and worth of Classical art and culture, far better than the ancient makers of it. Their outlook was that of St. Augustine of Hippo:

If those who are called philosophers, and especially the Platonists, have said aught that is true and in harmony with our faith, we are not only not to shrink from it, but to claim it for our own use from those who have unlawful possession of it. For, as the Egyptians had not only the idols and heavy burdens which the people of Israel hated and fled from, but also vessels and ornaments of gold and silver, and garments, which the same people when going out of Egypt appropriated to themselves, designing them for a better use, not doing this on their own authority, but by the command of God, the Egyptians themselves, in their ignorance, providing them with things which they themselves were not making a good use of; in the same way all branches of heathen learning have not only false and superstitious fancies ... but they contain also liberal instruction which is better adapted to the use of the truth, and some most excellent precepts of morality; and some truths in regard even to the worship of the One God are found among them.

Now these are, so to speak, their gold and silver, which they did not create themselves, but dug out of the mines of God’s providence which are everywhere scattered abroad.... These, therefore, the Christian, when he separates himself in spirit from the miserable fellowship of these men, ought to take away from them, and to devote to their proper use in preaching the Gospel.

St. Augustine’s argument for inculturation as a triumphal statement, as an assertion of the universal prerogative of Christianity, can apply to any ancient or foreign culture, not just to that of Greece or Rome or Egypt. The mines of God’s providence are everywhere scattered abroad. If the Metamorphoses can be moralized and read as a dim Christian allegory, so too can Norse and Celtic and Persian and Chinese mythology; if aught that is true in Platonism can be claimed for Christian use, so too can aught that is true in Confucianism or Advaita Vedanta, however much or little.

*******

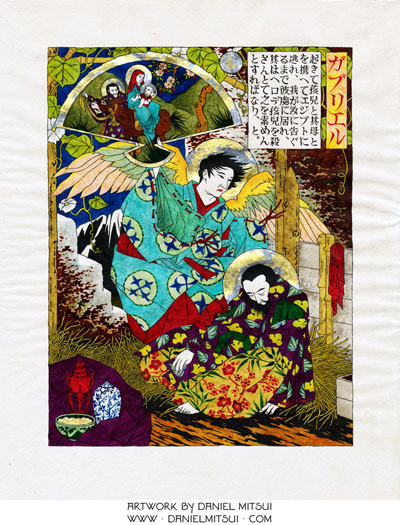

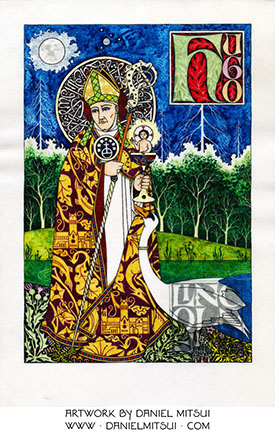

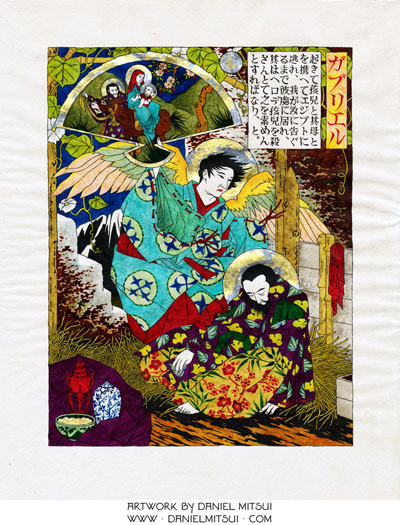

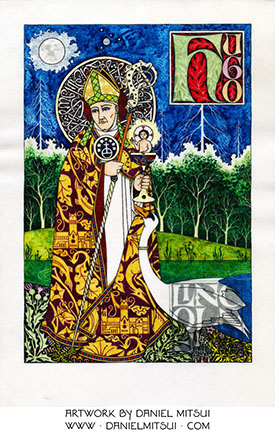

About seven years ago, one of my patrons asked me to draw St. Michael the Archangel in the style of a Japanese woodblock print. At the time, I had little knowledge of Oriental art, despite having some Japanese ancestors. I nonetheless undertook the challenge. The drawing became one of my most popular; similar commissions followed, in which I transposed traditional Christian iconography into this style.

Creating such works gave me a great appreciation for Japanese art, but I became uncomfortably aware that I was treating it as a context, and therefore as a larger thing than traditional Christian iconography. I have no desire to imitate the Humanists who gave the same treatment to Greek and Roman art, or the contemporary Christian artists who unquestioningly accept the conventions of electronic mass media.

Now, I rather identify those aspects of Japanese art that are agreeably Christian, and to include them in my drawings that are basically Gothic. An example is that in Japanese woodblock prints, as in Byzantine icons, almost no cast shadows are depicted. In Byzantine icons, this is deliberate; their perspective is heavenly, from a place where God illuminates everything. That was not the intention of the Japanese printmakers, but their treatment of light can be used to express the same religious idea in a work of graphic art.

The scholar Martin Lings had a similar observation to mine, on the affinity of Oriental and Gothic art. He wrote:

Having come to know some of the best examples of Hindu, Chinese and Japanese art and then as it were returning to their own civilization, many people find that their outlook has irrevocably changed. After looking at a great Chinese landscape, for example, where this world appears like a veil of illusion beyond which, almost visibly, lies the Infinite and Eternal Reality ... they find it difficult to take seriously a painting such as Raphael’s famous Madonna, or Michelangelo’s fresco of the Creation, not to speak of his sculpture, and Leonardo also fails to satisfy them. But they find that they can take very seriously, more seriously than before, some of the early Sienese paintings such as Simone Martini’s Annunciation, for example, or the statuary and stained glass of Chartres Cathedral....

The reason why medieval art can bear comparison with Oriental art as no other Western art can is undoubtedly because the medieval outlook, like that of the Oriental civilizations, was intellectual. It considered this world above all as the shadow or symbol of the next, man as the shadow or symbol of God.... A medieval portrait is above all a portrait of the Spirit shining from behind a human veil. In other words, it is as a window opening from the earthly on to the heavenly, and while being enshrined in its own age and civilization as eminently typical of a particular period and place, it has the same time, in virtue of this opening, something that is neither of the East nor of the West, nor of any one age more than another.

If Renaissance art lacks an opening onto the transcendent and is altogether imprisoned in its own epoch, this is because its outlook is humanistic; and humanism ... considers man and other earthly objects entirely for their own sakes as if nothing lay behind them. In painting the Creation, for example, Michelangelo treats Adam not as a symbol but as an independent reality; and since he does not paint man in the image of God, the inevitable result is that he paints God in the image of man.

The outlook of Gothic art, being intellectual and transcendent, is farsighted enough to include the whole of Christendom, and to see beyond it to all nations. It can be the basis for an urgently needed revival of artistic and cultural Christendom, and for its missionary effort.

*******

The treasures of Christian art and architecture are today endangered: by indifference and neglect, by misguided renovation, by war and revolution. They may be preserved for a time for the sake of national identity or lofty but indifferentist notions of cultural worth. But the Lindisfarne Gospels and Chartres Cathedral are things of this world, and will not last forever: Rust and moth consume, thieves break in and steal. More tragic than to lose such treasures is to lose the ability to make them; more tragic yet is to lose the desire to make them. That desire can only be provided by religious faith. It is religious faith that animates the tradition, that makes it live rather than linger.

It is the natural province of the Church to safeguard art and culture, even art and culture made by the foes of Ecclesia. It can welcome the genius of every nation and attune it to harmony. The need to do this should be felt in the present day, even more than at the time of Cassiodorus. Destructive forces are ascendant in all nations; all culture is at risk.

That includes, perhaps most especially, the historic art and architecture of Islamdom. Many Christians ignore differences within Islamdom and regard all of its culture as that of a common enemy. But many great works of Ottoman art were influenced by Sufi mysticism. The Safavids, under whom the stunning mosques of Isfahan were built and decorated, and under whom miniature painting flourished, were Shia. The Mughals built grand funerary monuments. Aspects of these cultures and their art are condemned as heretical and idolatrous by growing fundamentalist movements within Islamdom, and marked for destruction as readily as churches. In Saudi Arabia, for example, historic buildings and cemeteries are being razed and replaced with bare and empty constructions that express a different theological outlook.

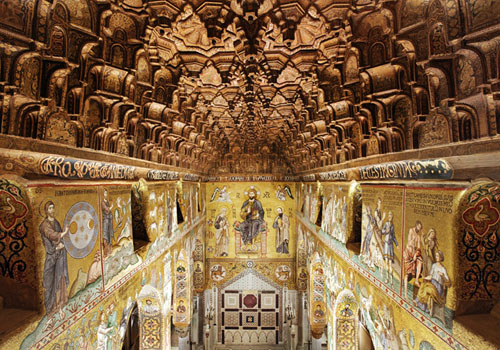

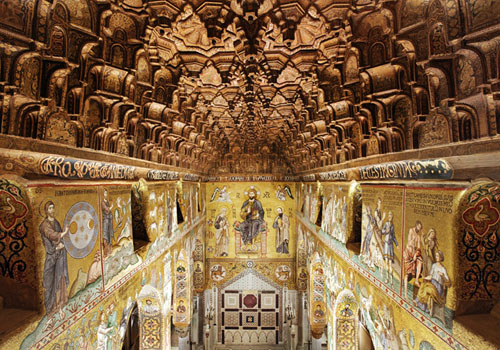

Now it is not my place to say whether this is, from an Islamic perspective, correct or not. As a Christian, I see extraordinary beauty in the historic art and architecture of Islamdom that should be preserved. Medieval Christian artists saw the same; they admired and borrowed its forms eagerly. In the Norman Kingdom of Sicily, they even employed its makers as collaborators. The Palatine Chapel at Palermo, whose ceiling is decorated with muqarnas, may be the most impressive result of their broadminded and generous consideration. I hope that Christian artists can yet again appreciate this art, and make a home for its best aspects within the Christian tradition, within International Gothic.

Ceiling of the Palatine Chapel at Palermo

This is one of my own ambitions. I am studying Islamic geometric design, miniature painting and calligraphy. My recent drawings include orthogonal letter patterns inspired by the decoration of Persian mosques and haloes filled with pseudo-Arabic script (the actual words that they form in my drawings are prayers and nomina sacra in Latin).

*******

Jesus Christ instructed his Apostles: Teach ye all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost. This Great Commission can be illustrated by figuratively baptizing the art of all nations. Doing this requires Christian artists to let go of historic and current enmities. Yes, for centuries Moors and Turks waged wars of conquest against Christendom. Japanese Buddhists long persecuted the Church with horrific brutality. The Romans fed the saints to lions; the culture preserved by Cassiodorus was the culture of Diocletian. Christian artists should not ignore any of that.

But they nonetheless should see truth, beauty and goodness in the cultural treasury of all nations, and fashion sacred art from it to honor Jesus Christ. This is the visual expression both of Christianity’s universal prerogative and its peculiar commandment: Love your enemies; do good to them that hate you and pray for them that persecute and calumniate you.

Photographic Image Credit:

Ceiling of the Monastery Church at Prüfening: The Wikimedia Commons

(https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ecclesia_Deckenmedallion.jpg)

Ceiling of the Palatine Chapel at Palermo: The Public Medievalist

(https://wwww.publicmedievalist.com/poet-mediterranean-ibn-hamdis/)

Works quoted or referenced:

Christopher De Hamel, A History of Illuminated Manuscripts, (London: Phaidon Press, 1994).

Bede, The Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation, translated by LC Jane, (London: JM Dent, 1910).

Janet Backhouse, The Lindisfarne Gospels, (London: Phaidon, 1981).

Gerald of Wales, Topographia Hiberniæ, quoted in The Book of Kells: Selected Plates in Full Color, (New York: Dover Publications, 1982).

Marc Drogin, Medieval Calligraphy: Its History and Technique, (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1989).

Emile Mâle, Religious Art in France: The Twelfth Century, translated by Marthiel Matthews, (Princeton University Press, 1978).

Volkmar Gantzhorn, The Christian Oriental Carpet, (Tübingen: Taschen, 1991).

Emile Mâle, The Gothic Image: Religious Art in France of the Thirteenth Century, translated by Dora Nussey, (New York: Icon Editions, 1972).

The Works of Aurelius Augustine, Bishop of Hippo, translated by Marcus Dods, (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1892).

Martin Lings, The Sacred Art of Shakespeare, (Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions International, 1998).